Abstract

The purpose of this report is to study expatriate management and international staffing relating to Samsung Electronics and suggest a practical recommendation for the company. The first section explores expatriate failure, expatriate performance and reward management, and talent management. Causes and costs of expatriate failure are identified, and the ways for increasing the expatriate success rate are provided. Also, the role of expatriate performance and reward management in MNCs and the challenges of distributing rewards associated with culture and institutions are discussed with example countries where Samsung Electronics’ subsidiaries are located. Lastly, different approaches and philosophies of talent management are explained, and Samsung Electronics’ approach towards talent management is identified.

In the international staffing section, the business strategy of Samsung Electronics is identified, and its implication for HRM is discussed. The differences between four international staffing approaches (ethnocentric, polycentric, geocentric, regiocentric) are evaluated, and Samsung Electronics’ current staffing approach is identified. At the end of the report, a recommendation for Samsung Electronics is suggested for its further improvement in employees’ morale, productivity, and performance, ultimately benefiting both the company and employees.

1.0 Introduction

Samsung Electronics (SE) is a multinational high-tech company headquartered in Suwon, Korea. It was founded in 1969 and operates three main business divisions: Consumer Electronics, IT and Mobile Communication, and Device Solutions, and has a vast product spectrum (Samsung Electronics, n.d.). The company’s flagship product is smartphones. Based on the number of smartphone users, the largest smartphone markets are China, India, and the U.S (O’Dea, 2021), and SE’s market share in these countries is 2 percent, 20 percent, and 25 percent respectively (Stat Counter, 2021).

The company has 268,000 employees, and 244 subsidiaries globally. The major subsidiaries are Harman International Industries, Smart Things, SEMES (Samsung Newsroom, 2021; Samsung Electronics, 2020). Since SE has various divisions, competitors differ according to the divisions. When it comes to the smartphone market alone, SE’s main competitors are Apple and Huawei (O’Dea, 2021). This report will explore expatriate management and international staffing in connection with SE and provide practical recommendations of ways that talent management and performance management can be improved.

2.0 Expatriate Management

One of multinational corporations’ (MNCs) major investments is expatriates. Expatriates, or international assignees, refer to employees working and temporarily residing abroad (Dowling et al., 2012). MNCs use expatriates for multiple purposes expecting the various benefits they will bring to the company. The IHR manager’s ability to effectively manage expatriates is fundamental to increasing success rates and preventing failure. This section will explore expatriate failure, performance and reward management, and talent management relating to SE.

2.1 Expatriate Failure

Dispatching expatriates is a double-edged sword for MNCs because it has both the potential for bringing large profits and causing significant losses. It is a high-risk activity, with an average of 16 to 40 percent of overseas assignments failing and the costs of approximately $1 million per failure. However, many MNCs use expatriates for traditional control, fostering entry into new markets, and promoting international management competencies (Shaffer et al., 1999).

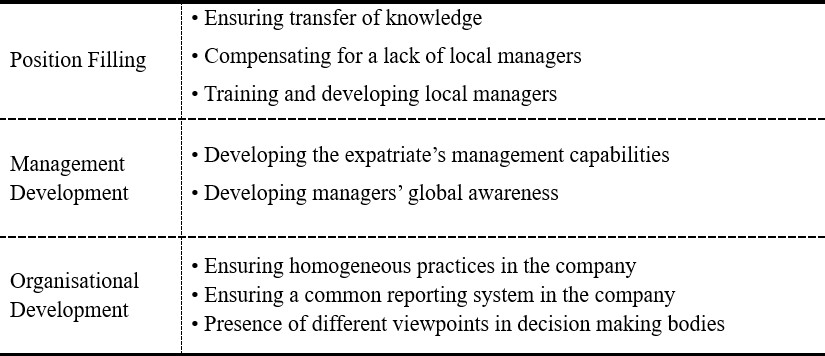

Table 1 Three General Corporate Motives for Transferring Employees

When an expatriate returns home country before completing assignments, or when his/her performance is poor, it is considered an expatriate failure. Companies should be aware that expatriate failure is very costly as it causes both direct and indirect costs. Direct costs are visible costs or losses. Relocation costs, including airfares, and training and expatriate’s salary are examples of direct costs. Indirect costs are invisible costs as it is hard to quantify in money terms. The MNC’s relations with clients, host government officials, local businesses might be damaged. Also, the company may lose its market share, and employees’ morale and productivity can be damaged (Dowling et al., 2012; Harzing & Ruysseveldt, 2004; Shay & Tracey, 1997).

It is very important for MNCs to identify the exact causes of failure for increasing success rates of expatriates and preventing losses of money and business. According to Shay & Tracey (1997) and Yeaton & Hall (2008), expatriate fails due to the failure of the expatriate or his/her family to adapt, personal or emotional immaturity, lack of technical expertise, inadequate knowledge of the host culture, and lack of repatriation efforts.

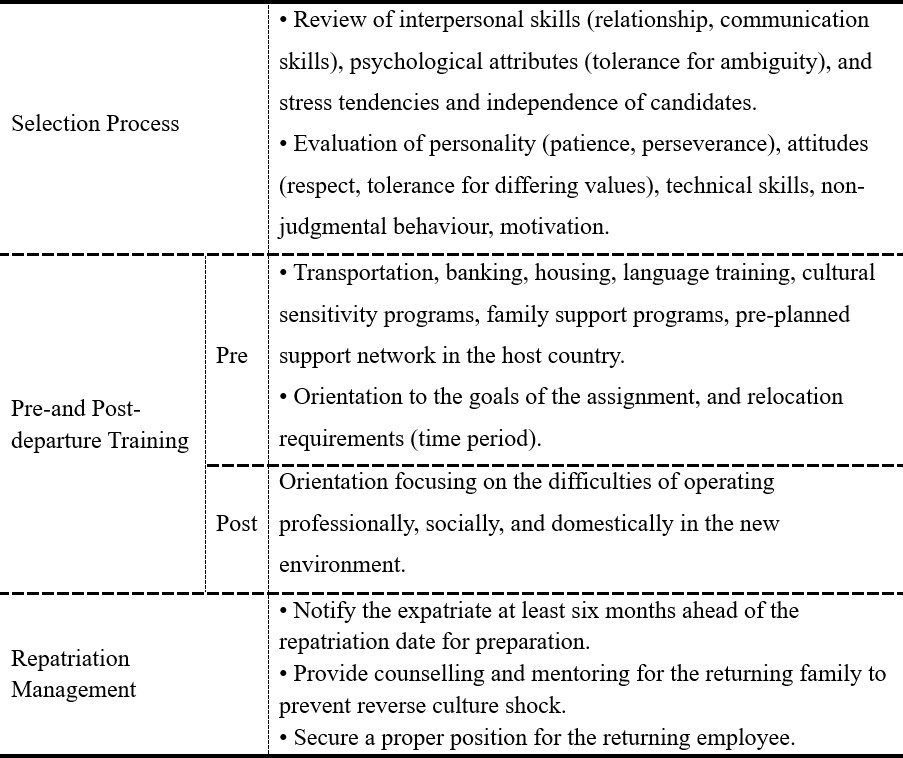

The selection process, pre-and post-departure training, and repatriation management are the key factors that can prevent expatriate failure. The most optimal expatriate can be selected through the selection process where the candidate’s ability to overcome obstacles, personality, and adaptability are analysed. Then, the adequate pre-and post-departure training should be provided to the selected expatriate so that he/she can be fully prepared to perform the overseas assignments successfully. Finally, repatriation management is crucial for the company to utilise the knowledge of the returning expatriate (Yeaton & Hall, 2008; Varner & Palmer, 2002). Table 2 shows what actions should be made in each factor.

Table 2 Ways to Prevent Expatriate Failure

According to Bateman & Snell (2004) and Chew (2004), the lack of understanding of the host culture is the leading cause of expatriate failure. For expatriates, being sent to a new culture means that they are ‘removed from the comfortable environment of their parental culture and placed in a less familiar culture’ (Sanchez et al., 2000, p. 96), which requires cross-cultural adjustment such as speaking in foreign languages, coping with culture shock, embracing different laws and customs, and interacting with local nationals (Harzing & Ruysseveldt, 2004). These are the barriers that expatriates should overcome and that the company should assist.

One of the cultural differences that might cause culture shock is the difference of high-and low-context cultures, distinguished by Hall (1973) depending on the way of communication. For example, Korea is a high-context culture where non-verbal clues are as important as spoken words. On the contrary, the U.S is a low-context culture where the verbal messages include most of the information (Merkin, 2009). Expatriates may find difficulties having smooth communication with local nationals due to this cultural difference.

SE provides extensive pre-and post-departure training such as orientation, language and culture sensitivity programs, cross-cultural communication, and training skills to the expatriates for ease of adjustment and preventing culture shock (Shih et al., 2005; Rani et al., 2016). Tung (1981) identified five cross-cultural training programs for expatriates: didactic training, cultural assimilator, language training, sensitivity training, and field experience, and SE can be said to be providing programs that help expatriates overcome cultural differences.

2.2 Expatriate performance and Reward Management

Expatriate performance management (EPM) is a part of MNC’s control system. EPM shapes corporate cultures through feedback and appraisals by rewarding employees for adopting required work behaviours, indirectly reinforcing normative control (Dowling et al., 2012; Fenwick et al., 1999). It is a fundamental component of strategic IHRM. Acting as a pipeline to the local market, EPM links HR functions to overall organisational strategies. MNCs use EPM to align the goals and their subsidiaries (Fee et al., 2011).

Reward management, a part of EPM, deals with strategies, policies, and procedures to ensure that employees’ contributions to the company are recognised by monetary, non-monetary, and psychological means. Its primary goal is to reward employees fairly, equitably, and consistently in accordance with their value to the company to achieve the company’s strategic objectives (Armstrong, 2007). However, there are challenges in reward management associated with cultural and institutional differences.

People’s ideas on how to distribute rewards differ depending on their cultural backgrounds (Leventhal, 1976), and this perceptual difference challenges IHR managers in distributing rewards justly. Crawley et al. (2013) classified countries according to the cultural characteristics based on Hofstede’s cultural dimensions (2001) and analysed the expected reward practices of each country.

According to the analysis, the U.S has an individualist culture where performance-related pay (PRP), bonuses and commission, employee share ownership plans are highly emphasised. Mexico, on the other hand, has high power distance culture. Rewards are seniority-based, and PRP and employee ownership plans are not frequently used in Mexico. These differences may challenge SE when rewarding expatriates in the U.S and Mexico.

Crawley et al. (2013) also emphasise the institutional factors affecting reward management. According to Newman et al. (2016), the labour unions have the most significant impact on international reward management among other institutional factors. Labour and employment laws concerning national minimum wages, equal pay, and taxation laws are also the institutional factors that significantly affect reward management (Festing & Tekieli, 2017). Understanding how these institutions differ from country to country is the critical challenge for IHR managers for effective and just reward management.

2.3 Talent Management

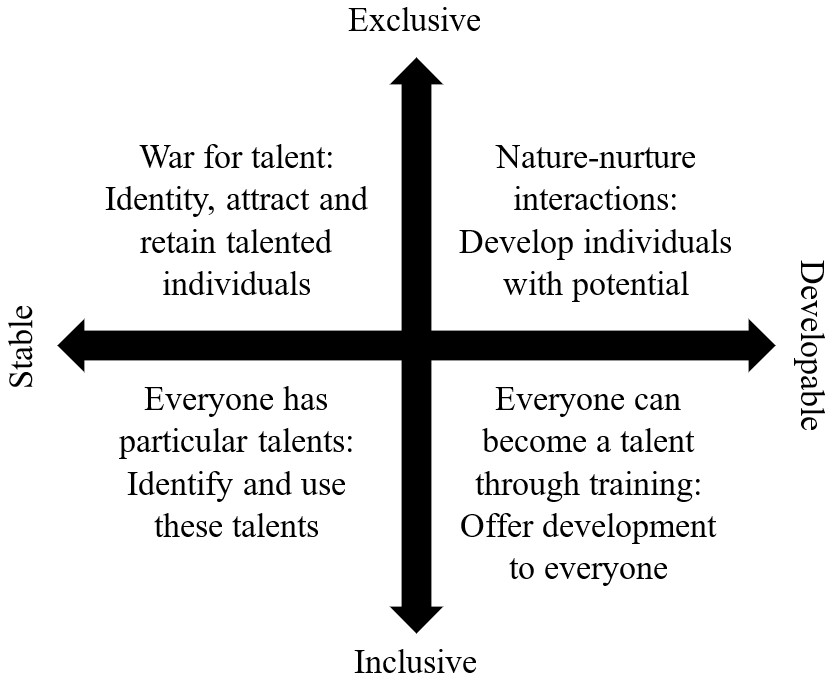

Global Talent management is crucial as it systematically identifies the focal positions that contribute to the company’s sustainable competitive advantage on an international scale. Also, it develops a pool of high-performing employees with high potential, and a differentiated HR architecture to fill the pivotal positions with the best available personnel of MNC sustainably (Collings et al., 2018). There are two approaches to talent: exclusive and inclusive. The exclusive approach aims to invest in retaining employees with valuable and unique skills, and talent is considered as rare. On the other hand, the inclusive approach sees talent as something that everyone has and aims to provide the same opportunity to all employees (Redman et al., 2017).

“A company is nothing but people” is SE’s core value that indicates how SE treats talents. According to SE’s sustainability report (2016), SE perceives that everyone is talented having unique competencies and potential, and it is committed to develop and nurture them further. This indicates that SE is taking inclusive approach towards talent management.

The SE’s philosophy underpinning its talent management can be derived by analysing the company through Figure 1. The philosophy is divided into four categories: Stable/Exclusive, Exclusive/Developable, Developable/Inclusive, Inclusive/Stable.

Figure 1 Talent Management Philosophy

As mentioned earlier, SE perceives that everyone is talented with unique competencies and potential and is providing various training programs to develop and nurture the employees further. This clearly matches with the philosophy of inclusive/stable (Everyone has particular talents).

This section covered the costs of expatriate failure and how to increase the success rate and prevent failure. Expatriate failure is very costly, but MNCs like SE are increasingly using expatriates providing various training programs/supports and developing performance/reward and talent management strategies to prevent failure. It can be concluded that training programs, performance, rewards, talent managements are essential for expatriate success.

3.0 International Staffing

International staffing is a core initiative in global talent management, including recruitment and selection processes (Kang & Shen, 2016). It deals with ‘critical issues faced by MNCs concerning the employment of home, host and third-country nationals to fill key positions in their headquarters and subsidiary operations’ (Scullion & Collings, 2006, p. 3). This section will explore the business strategy, international staffing approach, and international staffing plan for SE.

3.1 Business Strategy

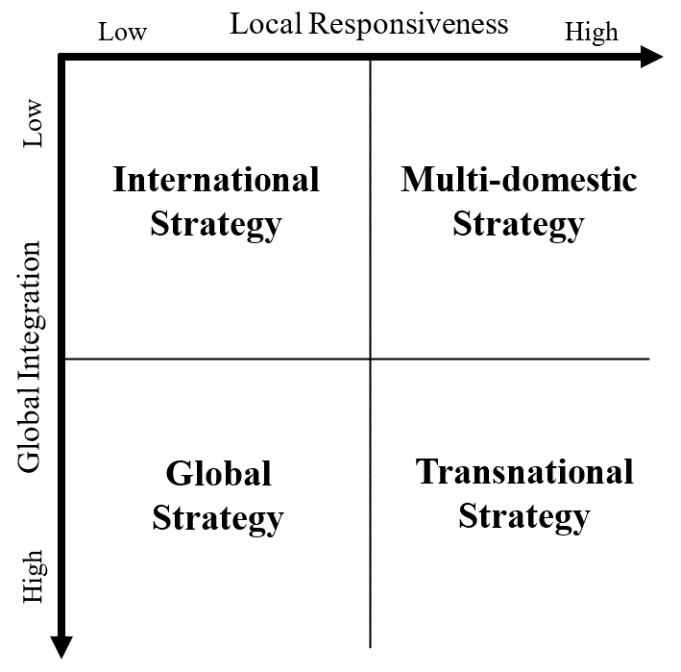

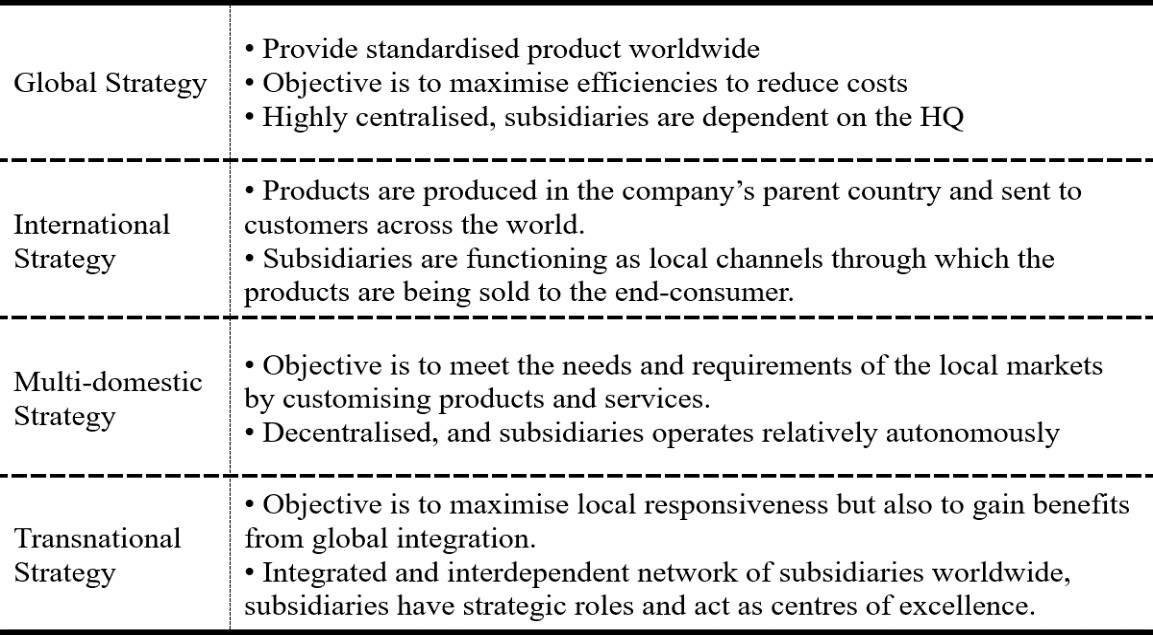

The international business strategy can be divided into four categories: global, international, multi-domestic, and transnational strategies. An MNC’s international business strategy is identified based on global integration and local responsiveness (Buckley et al., 2018). Figure 2 shows the four types of business strategies.

Figure 2 International Business Strategies

Global strategy is high integration and low responsiveness, international strategy is low integration and low responsiveness, multi-domestic strategy is low integration and high responsiveness, and transnational strategy is high integration and high responsiveness. Table 3 describes the characteristics of each strategy

Table 3 Characteristics of Each International Business Strategy

SE uses a global strategy as it makes extensive economies of scale with standardized products worldwide and aims to reduce costs as much as possible by selecting ideal locations where tax reduction or other benefits are provided (Simonin, 2014). As the arbitrary decisions of subsidiaries cannot be made in a global strategy, active coordination of HRs in charge of global activities with decision rights is required (Collis & Wiley, 2016).

3.2 International Staffing Approach

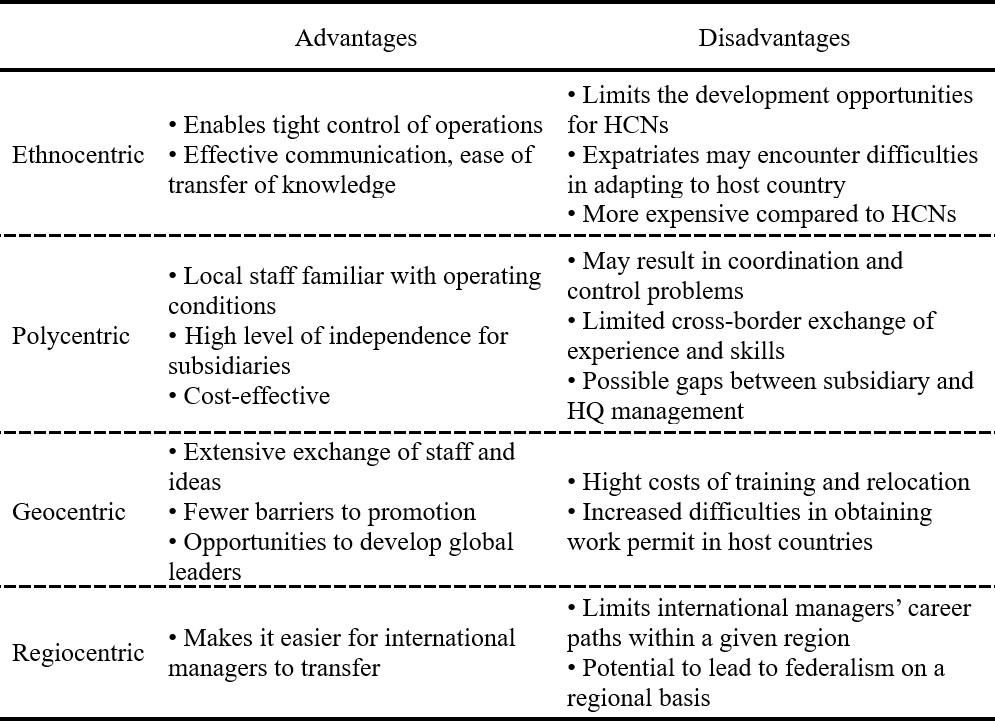

Employees are the most important of all corporate resources. Hence, it is essential to take an appropriate staffing approach to attract and retain high-quality staff (Buckley et al., 2018). There are four international staffing approaches: ethnocentric, polycentric, geocentric, and regiocentric.

The ethnocentric staffing approach appoints the parent country nationals (PCN) to the top position, whereas the polycentric approach appoints the host country nationals (HCN). The geocentric approach appoints the best personnel regardless of nationality and may include third-country nationals (TCN). Finally, the regiocentric approach appoints the best personnel within a particular region (Kang & Shen, 2016; Buckley et al., 2018). Table 4 contains a comparison of the four approaches.

According to Almutairi et al. (2019), SE is taking a geocentric staffing approach to improve its operational efficiency and develop global strategies. By employing the geocentric approach, SE overcame the cultural and institutional barriers and can use human resources effectively (Lee et al., 2011).

Table 4 Comparison of the Four Staffing Approaches

3.3 Effective International Staffing Plan

MNCs use their employees from different countries to form a staffing composition for their subsidiaries. There are three options for MNCs to select from PCNs, HCNs, or TCNs for the key management positions in host country units (Colakoglu et al., 2009). In SE’s staffing strategy (geocentric approach), all of PCNs, HCNs, and TCNs are used for key positions as the objective of the approach is to choose the best person regardless of nationality. Thus, it is proposed for SE to appoint among all PCN, HCN, and TCN according to their required ability.

This section explored the business strategy, international staffing approach of SE and proposed a staffing plan for the company. The key findings of this section are that SE is using a global strategy and taking a geocentric staffing approach.

4.0 Conclusion and Recommendations

This report is divided into two main sections, covering expatriate management and international staffing, in connection with Samsung Electronics. The key findings in the first section are that SE is increasingly using expatriates despite the risk of failure and developing and practicing appropriate strategies for successful expatriate activities. The second section found that SE uses a global strategy and takes an inclusive approach towards talent management and the geocentric staffing approach.

It is recommended for SE to build an organisational culture that supports work-life balance for a better organisational image, which will attract desirable employees. According to Redman et al. (2017), extra working hour causes discouragement of employees. However, employees’ morale, productivity, and performance can be extensively improved by initiating work-life balance practices (Lazar et al., 2010). This practice may be a win-win strategy for SE as it benefits both the employees and the company in enhancing its overall performance and productivity.

Reference List

Feature image : Samsung Electronics headquarters in Seoul, South Korea, file (AFP)

Almutairi, M., Mehta, S., Al Rashidi, F., Villa, M. A., & Anggawinata, F. (2019). Analysis of Samsung’s Internationalization Process and The Strategies Implemented to Generate an Effective Positioning of Its Brand and Products in Foreign Markets. Journal of the Community Development in Asia, 2(1), 27–39.

Armstrong, M. (2007). A Handbook of Employee Reward Management and Practice (2nd ed.). Kogan Page.

Bartlett, C. A., & Ghoshal, S. (1989). Managing Across Borders: The Transnational Solution. Harvard Business School Press.

Bateman, T., & Snell, S. (2004). Management: Then New Competitive Landscape (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Buckley, P. J., Enderwick, P., & Cross, A. R. (2018). International business. Oxford University Press.

Buckley, P. J., & Ghauri, P. N. (2015). International Business Strategy: Theory and Practice. Routledge.

Chew, J. (2004). Managing MNC Expatriates through Crises: A Challenge for International Human Resource Management. Research and Practice in Human Resource Management, 12(2), 1–30.

Colakoglu, S., Tarique, I., & Caligiuri, P. (2009). Towards a Conceptual Framework for the Relationship between Subsidiary Staffing Strategy and Subsidiary Performance. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20(6), 1291–1308. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190902909822

Collings, D. G., Mellahi, K., & Cascio, W. F. (2018). Global Talent Management and Performance in Multinational Enterprises: A Multilevel Perspective. Journal of Management, 45(2), 540–566. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318757018

Collis, D. J., & Wiley, J. (2016). International Strategy: Context, Concepts and Implications. Wiley.

Crawley, E., Swailes, S., & Walsh, D. (2013). Introduction to International Human Resource Management. Oxford University Press.

Dowling, P. J., Festing, M., & Engle, A. D. (2012). International Human Resource Management (6th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Edström, A., & Galbraith, J. C. (1977). Transfer of Managers as a Co-ordination and Control Strategy in Multinational Organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 22(2), 248–263.

Fee, A., McGrath-Champ, S., & Yang, X. (2011). Expatriate Performance Management and Firm Internationalization: Australian Multinationals in China. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 49(3), 365–384. https://doi.org/10.1177/1038411111413529

Fenwick, M. S., De Cieri, H. L., & Welch, D. E. (1999). Cultural and Bureaucratic Control in MNEs: The Role of Expatriate Performance Management. Management International Review, 39(3), 107–124.

Festing, M., & Tekieli, M. (2017). Global reward management. The Routledge Companion to Reward Management, 209–221. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315231709-21

Hall, E. T. (1973). The Silent Language. Anchor Books.

Harzing, A.-W., & Ruysseveldt, J. V. (2004). International Human Resource Management (2nd ed.). Sage.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations across Nations (2nd ed.). Sage.

Kang, H., & Shen, J. (2016). Global Talent Management: International Staffing Policies and Practices of South Korean Multinationals in China. International Business and Management, 32, 25–48. https://doi.org/10.1108/s1876-066×20160000032019

Lazar, I., Osoian, C., & Ratiu, P. (2010). The Role of Work-Life Balance Practices in Order to Improve Organizational Performance. European Research Studies, 8(1), 201–213.

Lee, S.-H., Bryan, G. E., Gildas, H., Wakpo, B., Koh, J., Singh, S., & Kim, H.-W. (2011). Globalization of Korean IT Companies: Opportunities and Strategies. International Conference on Information Resources Management, 1–16.

Leventhal, G. S. (1976). Fairness in Social Relationships. Contemporary Topics in Social Psychology, 39–211.

Liu, X., & Shaffer, M. A. (2005). An Investigation of Expatriate Adjustment and Performance: A Social Capital Perspective. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 5(3), 235–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595805058411

Merkin, R. S. (2009). Cross-cultural Communication Patterns – Korean and American Communication. Journal of Intercultural Communication, 20, 1–14. https://doi.org/http://www.immi.se/intercultural/

Meyers, M. C., & van Woerkom, M. (2014). The Influence of Underlying Philosophies on Talent Management: Theory, Implications for Practice, and Research Agenda. Journal of World Business, 49(2), 192–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2013.11.003

Newman, J., Gerhart, B., & Milkovich, G. (2016). Compensation (12th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

O’Dea, S. (2021). Smartphone Users by Country Worldwide 2021. Statista; https://www.statista.com/statistics/748053/worldwide-top-countries-smartphone-users/

Rani, H. M. N. S., Zuber, F., Yusoof, M. S., Zamziba, M. N., & Toriry, S. A. (2016). Managing Cross-Cultural Environment in Samsung Company: Strategy in Global Business. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 6(11), 605–613. https://doi.org/10.6007/ijarbss/v6-i11/2445

Redman, T., Wilkinson, A., & Dundon, T. (2017). Contemporary Human Resource Management: Text and Cases (5th ed.). Pearson Education.

Samsung. (2016). Samsung Sustainability Report 2016.

Samsung Electronics. (n.d.). Company Info | About Us. https://www.samsung.com/uk/about-us/company-info/

Samsung Electronics. (2020). 2020 Half-year Business Report (pp. 1–212).

Samsung Newsroom. (2021). FAST-FACTS. https://news.samsung.com/global/fast-facts

Sanchez, J. I., Spector, P. E., & Cooper, C. (2000). Adapting to a Boundaryless World: A Developmental Expatriate Model. Academy of Management Executive, 14, 96–107.

Scullion, H., & Collings, D. G. (2006). Global Staffing. Routledge.

Shaffer, M. A., Harrison, D. A., & Gilley, K. M. (1999). Dimensions, Determinants, and Differences in the Expatriate Adjustment Process. Journal of International Business Studies, 30(3), 557–581.

Shay, J., & Tracey, J. B. (1997). Expatriate Managers: Reasons for Failure and Implications for Training. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 38(1), 30–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/001088049703800116

Shih, H., Chiang, Y., & Kim, I. (2005). Expatriate performance management from MNEs of different national origins. International Journal of Manpower, 26(2), 157–176. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437720510597658

Simonin, D. (2014). International Strategy: The Strategy of Samsung Group. 1–14. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.5188.7440

Stat Counter. (2021). Mobile Vendor Market Share. https://gs.statcounter.com/vendor-market-share/mobile/south-korea

Tung, R. L. (1981). Selection and Training of Personnel for Overseas Assignments. Colombia Journal of World Business, 16(2), 67–78.

Varner, I., & Palmer, T. (2002). Successful Expatriation and Organisational Strategies. Review of Business, 23, 8–12.

Yeaton, K., & Hall, N. (2008). Expatriates: Reducing Failure Rates. Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance, 19(3), 75–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcaf.20388