Mergers and acquisitions (M&A) take place for various purposes among many companies domestically and internationally. As international M&A occurs among companies from different countries with different cultures, the role of human resource managers is crucial at all pre-and post-integration phases compared to domestic M&A. The focus of this report is on the international M&A. It explores the case of Samsung Electronics’ acquisition of TeleWorld Solutions, analysing and assessing the cultural and institutional differences of the mother countries (South Korea, the U.S), and recommending appropriate HR practices for a successful M&A.

The difference in the political, economic, social environment (PES) and institutions of Korea and the U.S were analysed. These analyses figured out that the impact of institutions on organisational behaviours and HR practices is significant, and there is a notable difference in PES environments between Korea and the U.S. Also, the cultural differences of the two countries are analysed using Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions. The indexes of individualism and long-term orientation showed the most significant difference in scores. However, other cultural dimensions also demonstrated considerable differences in scores, indicating that Korea and the U.S are culturally divergent countries.

They differ in the way of communication according to Hall’s theory of cross-cultural communications as well. Korea is a high-context culture where indirect non-verbal clues are as crucial as the words that are spoken. On the contrary, the U.S is a low-context culture where the words being spoken are explicitly delivered to the listener. Based on the analyses made in this paper, it is recommended for Samsung to take a preservation approach when acquiring TWS and employ low-context communication when cross-culturally communicating.

The smartphones industry and telecommunications industry are closely correlated. Electronic devices such as smartphones need to be connected to the information communications network for a full-scale operation. The infrastructure that allows smartphones to connect to networks is built by the telecommunication industry (Beers, 2021).

Samsung Electronics is a Korean electronics manufacturer founded in 1969 (Samsung Electronics, n.d.). It is one of the biggest smartphone manufacturers worldwide, with an approximate mobile vendor market share of 64 percent in Korea and 28 percent globally (Statcounter GlobalStats, 2021). The number of employees is 287,439, and its revenue is approximately £146.3 billion (Samsung Newsroom, 2021). Major competitors are LG Electronics, Apple, HP, Sony, and Huawei (Craft, 2021). It is hard to define Samsung’s customer profile because it has multi-segment positions covering a full range of customers (Dudovskiy, 2017).

TeleWorld Solutions is a telecommunication company headquartered in Virginia. It was founded in 2002 and provides networking services delivering consulting, network design, optimisation, and cloud services, to various companies across the U.S (Treger, 2020; TeleWorld Solutions, 2019). Its revenue is approximately £1.11 million, and it has 150 employees (Dun & Bradstreet, 2021). The company’s main competitors are Plume, O2, Helium, and Fon (Craft, 2021).

Several analyses and assessments on the cultural and institutional differences between the two mother countries of Samsung and TWS through this report and suggestions/recommendations related to HR practices for a successful M&A will be provided in the end based on the analysis.

Cultural Analysis of South Korea and the U.S

Culture is a code of norms, attitudes, values, and ways of thinking that people learn in their social environments such as family, schools, workplaces, and countries, and they determine how people perceive themselves and the world. (Browaeys & Price, 2019). Therefore, culture can be defined as “the collective mental programming of the human mind which distinguishes group of people from another” (Köster, 2009, p. 99), and this mental program is deeply involved in people’s overall lives.

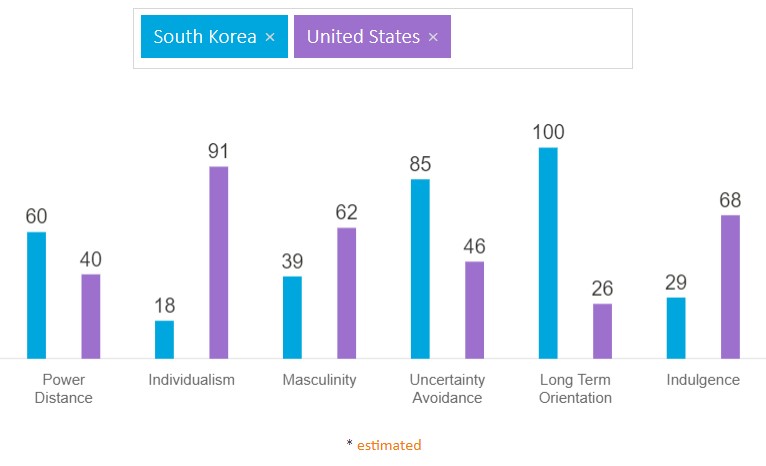

Hofstede created cultural dimensions, a framework for measuring the national cultures with scores in each of the dimensions in which cultures differ from each other (Köster, 2009), and the six cultural dimensions are listed in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Cultural Comparison Between South Korea and the U.S

Figure 1 is a comparison of South Korea and the U.S on the six cultural dimensions. When power distance is small, dependence of subordinates on bosses is less, and the relationship between bosses and subordinates is interdependent. On the other hand, when power distance is large, the dependence of subordinates on their bosses is significant, and it is harder for subordinates to approach their bosses. At a score of 60, South Korean organisations are likely to have hierarchical structures, whereas, at a score of 40, organisations in the U.S. tend to have horizontal structures (Hofstede et al., 2010).

The dimension of individualism versus collectivism shows the relationship between an individual and the group he or she belongs to. South Korea scored 18 on individualism index, which means Koreans tend to cooperate in groups. The U.S, on the other hand, scored 91 on the individualism index. In an individualistic culture, employees act in their interests, and work must be organised to align these self-interests with those of employers, while employees in a collectivist culture act according to the interests of their group, although they do not always coincide with their interests (Hofstede et al., 2010).

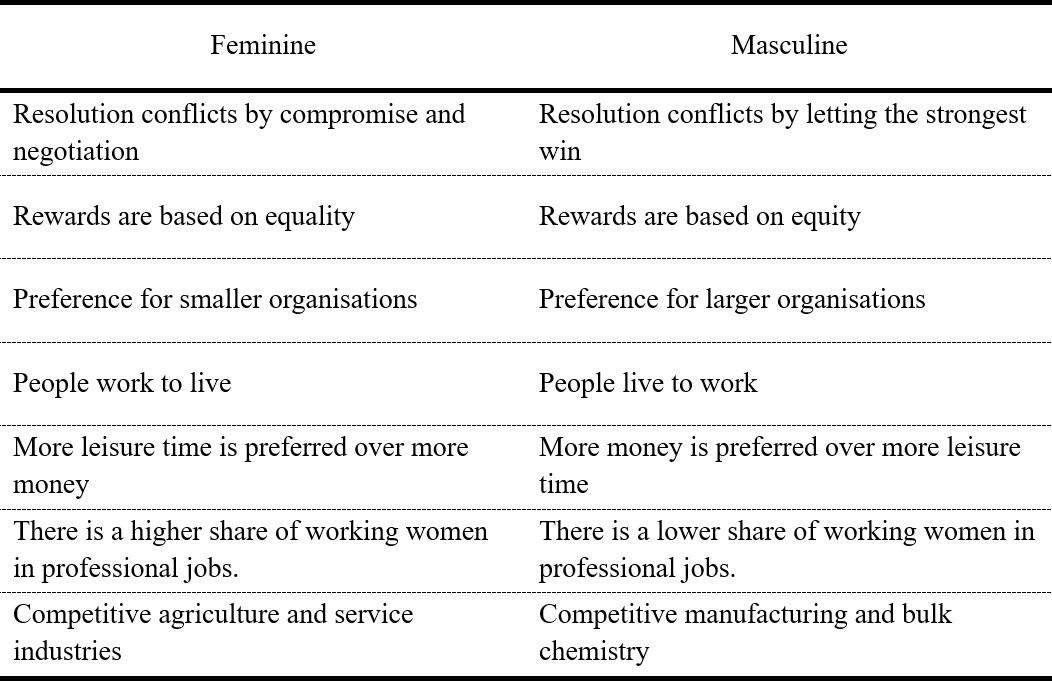

The masculinity-femininity index gauges the degree of desirability of assertive behaviour (masculinity) and the desirability of modest behaviour (femininity). South Korea scored 39, and the U.S scored 62 on this dimension, which means that South Korea is a more feminine society and the U.S is a more masculine society. “Intuition and consensus” represent a feminine society, and “decisive and aggressive” represent a masculine society (Hofstede et al., 2010). Organisational behaviours differ notably according to the types of society. Major differences are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1 Major Differences Between Feminine and Masculine Societies

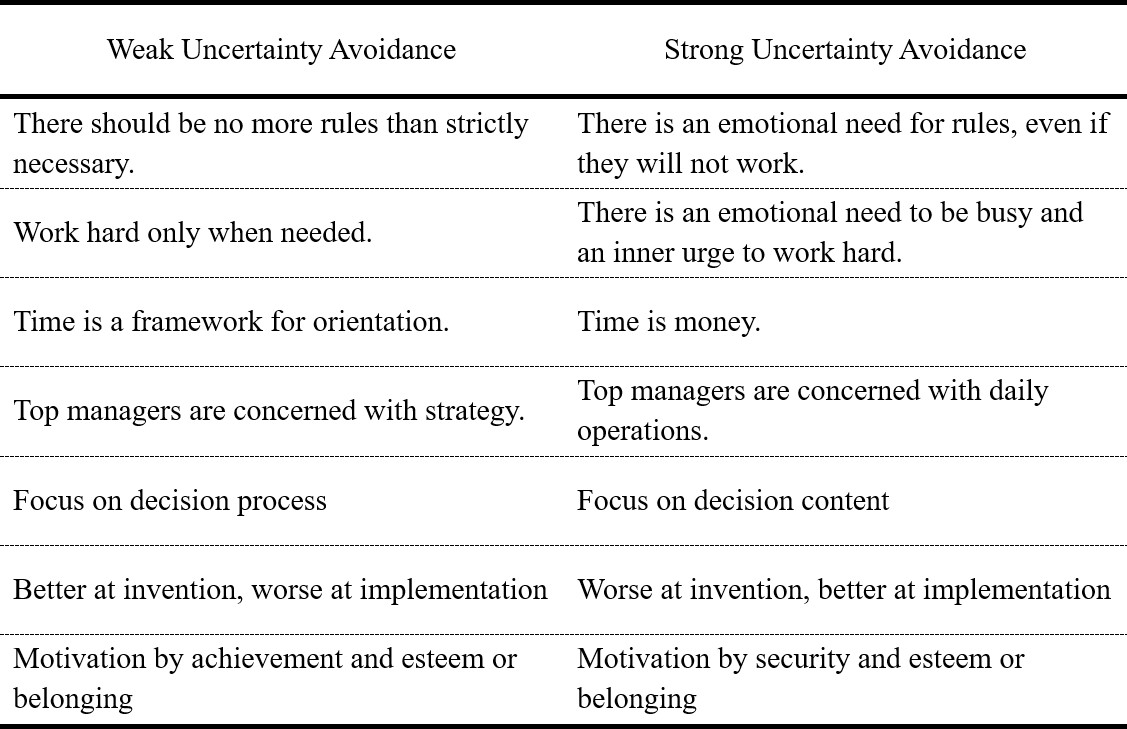

The uncertainty avoidance index shows the extent to which society is willing to accept and deal with uncertainty. South Korea scored 85, indicating that it is an uncertainty-avoiding country, while the U.S scored 46, which is the opposite of South Korea. There are fewer employer changes, and it is hard to balance work and life in organisations in a strong-uncertainty-avoidance society, while there are more employer changes and the term of services are shorter in organisations in a weak-uncertainty-avoidance society (Hofstede et al., 2010). Other differences in organisational behaviours are listed in Table 2.

Table 2 Differences Between Weak and Strong Uncertainty-Avoidance Societies

The following cultural dimension is the long-term versus short-term orientation. A society with a high score on this dimension aims at perseverance and thrift, which are virtues that promote future rewards, while a society with a low score aims to foster virtues related to social obligations. At a score of 100, Korea is a long-term oriented country, and the U.S is short-term oriented, scoring 26. The work values of these two groups are contradictory. Main work values in Korean society are learning, honesty, adaptiveness, accountability, and self-discipline, whereas freedom, rights, achievement, and thinking for oneself are valued in the U.S (Hofstede et al., 2010).

The indulgence versus Restraint dimension is the extent to which people try to control their desires and drives. South Korea scored 29, indicating that it is a restraint society. The U.S, on the other hand, is an indulgent society with a score of 68. People in a restraint society focus more on controlling desire than on leisure time and feel that indulging is somewhat wrong, while the idea of “work hard and play hard” prevails in an indulgent society (Hofstede et al., 2010; Hofstede Insights, 2021).

Institutional analysis of South Korea and the U.S

The institutional approach to IHRM begins with the understanding that organisations’ management and businesses have different institutional foundations depending on the country (Edwards & Rees, 2005), and the institutions are closely related to IHRM as they have a significant impact on various HRM activities, which include: recruitment and selection, employment conditions and contracts, performance management systems, rewards structures, redundancy payments, company pensions, and training and development (Crawley et al., 2013).

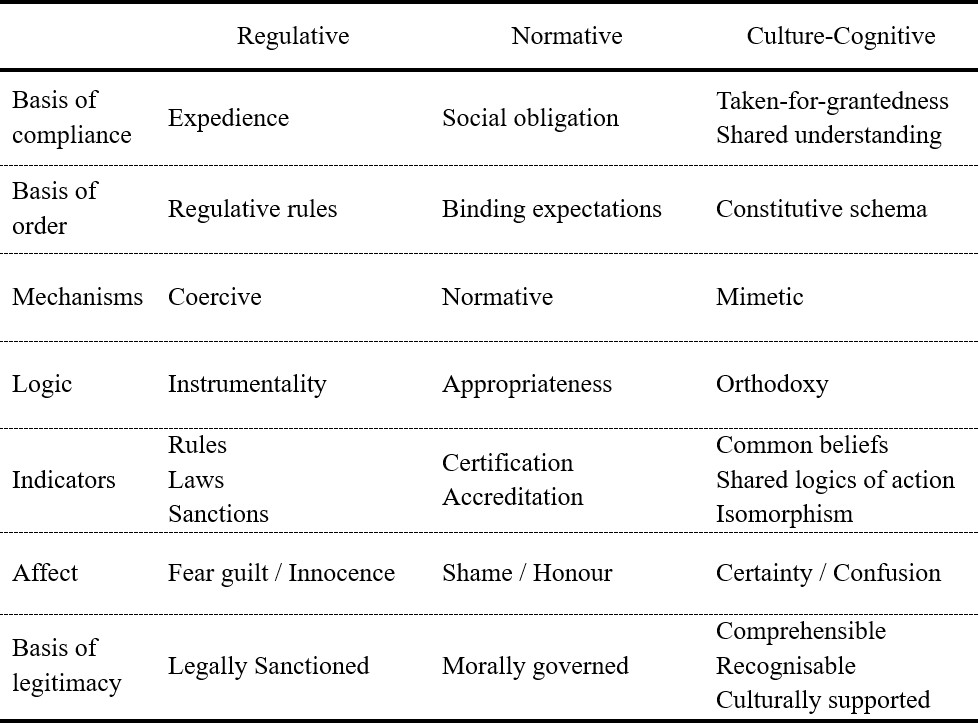

According to Scott (2014), “institutions comprise regulative, normative, and cultural-cognitive elements (three pillars of institutions, see Table 3) that, together with associated activities and resources, provide stability and meaning to social life” (p. 56). It is not entirely legitimate, but neither can it be wholly ignored (March & Olsen, 1984). The regulative, normative, and cultural-cognitive elements are the pillars by which institutions being supported. The regulative pillar refers to the regulative aspects of institutions. It includes legislation, monitoring and sanctioning to affect future behaviours using rewards and punishments (Scott, 2014), and the regulatory context acknowledges that HRM is an organisational function and that the organisation itself is an institution of regulation (Wilkinson, 2019).

The normative pillar includes values and norms and emphasises introducing a prescriptive, evaluative, and obligatory dimension into social life through normative rules. It defines organisations’ objectives and designates appropriate ways to pursue them simultaneously (Scott, 2014). The cultural-cognitive pillar is a “shared conception that constitutes the nature of social reality and creates the frames through which meaning is made” (Scott, 2014, p. 67).

Table 3 Three Pillars of Institutions

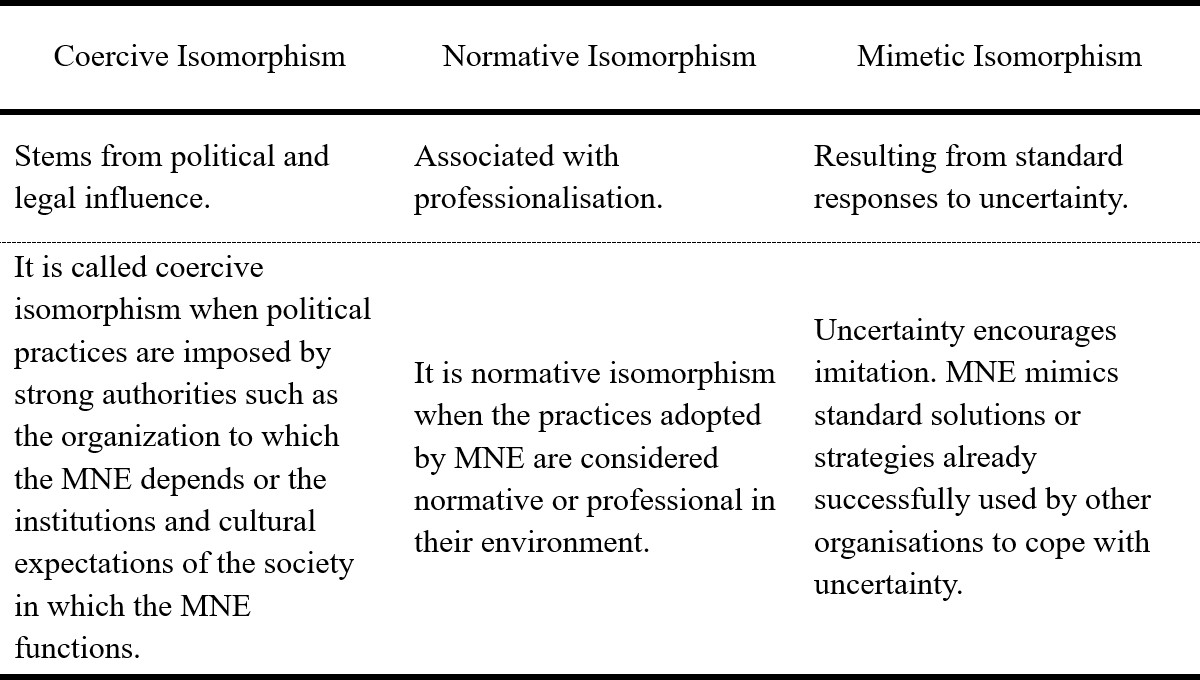

Isomorphism, along with neo-institutionalism, is a theory that influences IHRM. Institutional isomorphism is a process of restraint that forces one individual in a population to imitate others facing the same environmental situation (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). It is the result of processes that stimulate the spread of ideas, practices, and prescribed structures among organisations (Greenwood, 2017). There are three mechanisms of institutional isomorphism: coercive, normative, and mimetic isomorphisms, explained in Table 4.

Table 4 Three Mechanisms of Institutional Isomorphism

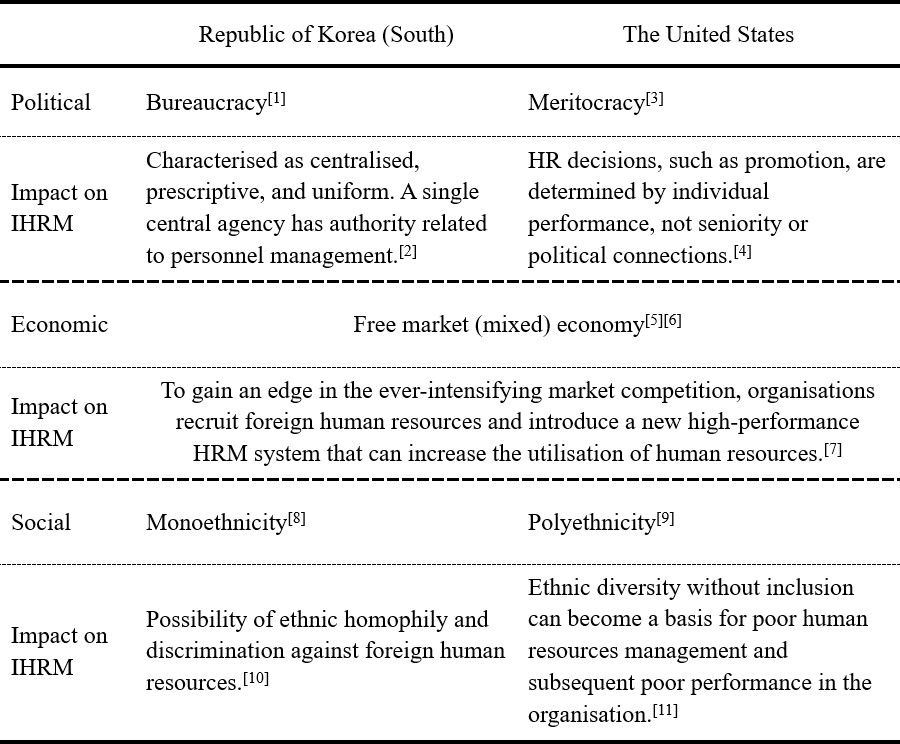

South Korea and the U.S have different political, economic, and social environments. As explained above, both neo-institutionalism and isomorphism emphasise the power of institutions and their influences on organisational activities in various ways. The adopted practices are not for effectiveness but due to the institutional forces (Bae & Rowley, 2001). Table 5 demonstrates how the two countries’ political, economic, and social environments differ and how they affect the IHRM practices.

Table 5 Comparison of Political, Economic, and Social Difference of Korea and the U.S

In section 1, cultural differences between Korea and the U.S are analysed using Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. Also, the impact of institutions on organisational behaviours and IHRM were assessed by applying theories of neo-institutionalism and isomorphism. Korea and the U.S have significantly different cultural and institutional backgrounds, which are the factors that IHR managers must deal with for a successful international M&A. The following section will explore the integration strategies and the role of IHRM for an effective M&A.

M&A Rationale and Integration Strategy

One of the most prominent smartphone manufacturers globally, Samsung Electronics, has acquired TeleWorld Solutions (TWS) in 2020, to accelerate the expansion of the 5G network in the United States to meet the customers’ growing needs for a 5G network and create new technological opportunities. TWS, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Samsung Electronics, complements Samsung’s growth among network infrastructure clients while maintaining its services for existing customers (Samsung Newsroom, 2020).

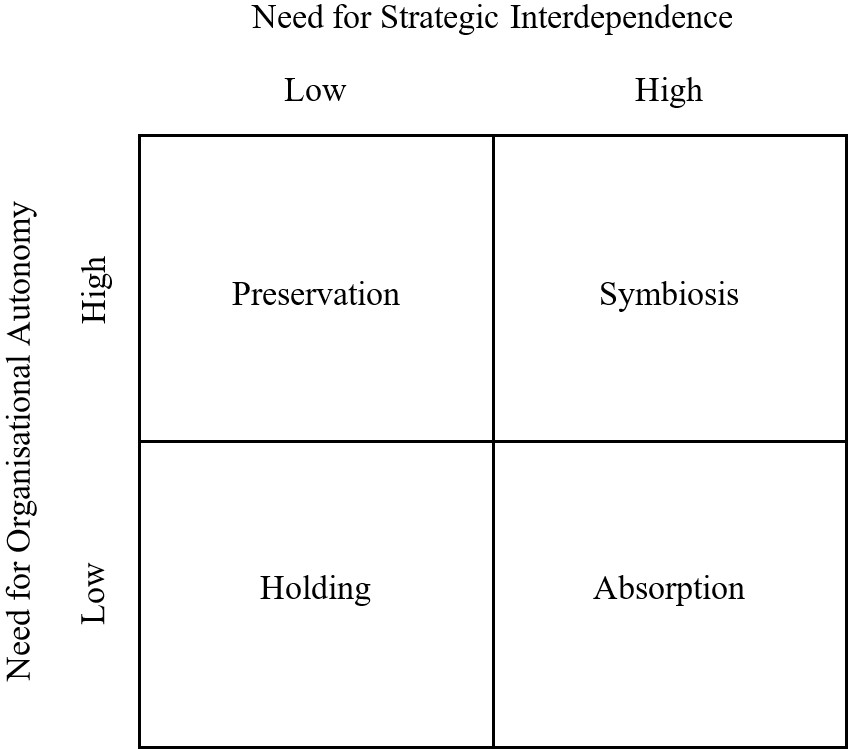

Adequate integration is essential because the effectiveness of the acquisition highly depends on how well the integration promotes the acquisition objectives (Fredriksson & Weidman, 2014). Haspeslagh and Jemison (1991) identified four integration approaches: Absorption, Preservation, Symbiosis, and Holding (see Figure 2), each of which is determined by the strategic interdependencies and the need for organisational autonomy. The explanation on how they differ from each other is as follow:

• Absorption takes place when the objective is to achieve consolidation and rationalisation as quickly as possible.

• Preservation preserves the autonomy and identity of the acquired company. Values come from the expansion of market and product and new resources.

• Symbiosis seeks to balance autonomy and interdependency. Both boundary preservation and boundary permeability and a gradual process must be ensured.

• Holding creates value from financial transfers and risk-sharing without intention of integrating (Haspeslagh & Jemison, 1991; Lasserre, 2018).

Figure 2 Four Integration Approaches.

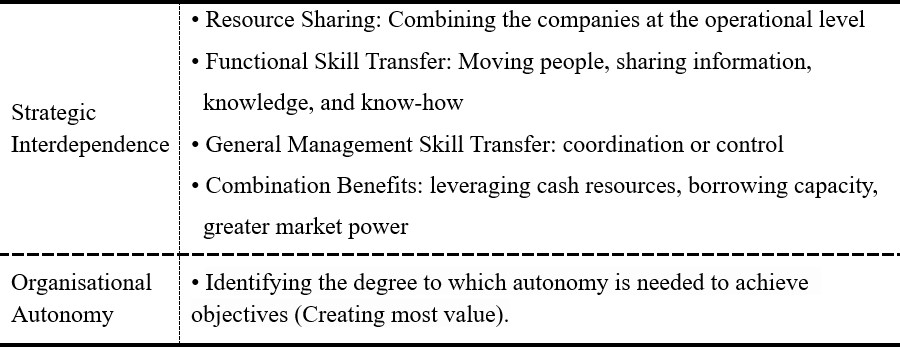

To select the optimal type of integration approach for Samsung, the level of need for interdependence and organisational autonomy must be analysed. Table 6 shows the standards for levels of autonomy and interdependence.

Table 6 Strategic Interdependency and Organisational Autonomy.

Samsung seeks to expand its market into networking service by exploiting TWS’ resources and technology while preserving the identity and autonomy of TWS simultaneously. Given all the information above, a preservation approach is recommended for Samsung when acquiring TWS.

Role of IHRM in implementing effective M&A

International M&As lead to changes in ownership rather than simply changes in operational strategies. Thus, appropriate and effective IHRM is essential for a successful M&A (Reiche et al., 2016). As international M&A is a process of two different organisations with different people from different cultures being consolidated, there are HR challenges during the pre and post phases of acquisition.

The pre-acquisition stage is a decision-making stage. The M&A decision, calculation of the acquired company’s potential value, and negotiation of the deal occur in this stage. On the other hand, post-acquisition phase, the most important source of success or failure, is managerial processes involved in the consolidation of the merged company (Lasserre, 2018).

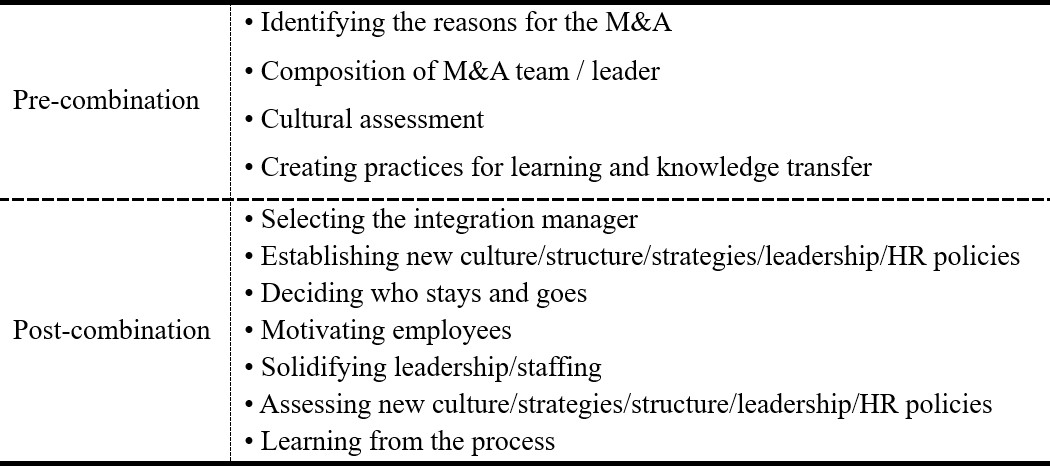

As the cultural and institutional differences are analysed above, Korea and the U.S are very distinctive countries. The more significant cultural differences they have, the more HR challenges they may have in the process of M&A. The issues in pre and post phases of acquisition are described in Table 7.

Table 7 HR Issues in Global M&A

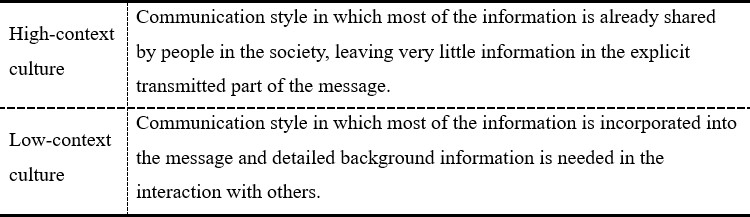

The role of IHRM is crucial for a smooth and active communication among the employees in the post-acquisition phase (Cahng-Howe, 2019). Since two companies from different cultures have merged, there are also differences in communication methods. Hall (1973) distinguished high- and low-context cultures depending on preferred way of communication. Table 8 compares the high- and low-context cultures.

Table 8 Comparison of High- and Low-context Cultures

The cultural differences affect business behaviours as well. In high-context cultures, interpersonal relations are valued in deciding whether to enter into business agreements, while the specific terms of a transaction is emphasised in low-context cultures (Griffin & Pustay, 2020). According to Merkin (2009), Korea is categorised as high-context culture, whereas the U.S is a low-context culture. Hence, the possibility of misunderstanding during negotiation or meeting is high when processing M&A.

Barkai (2008) suggests that HR managers, as mediators between employees from different cultures, should employ a low-context approach to prevent misunderstanding when communicating. Therefore, in the case of Samsung’s acquisition of TWS, it is recommended to employ more low-context communication when exchanging information between Samsung and TWS to minimise any possibilities of misleading or misapprehension.

Conclusion

Through the study on Samsung Electronics’ acquisition of TWS, cultural and institutional differences between the two mother countries (S. Korea, the U.S) are analysed using several theories, including Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, PES, integration approach, and Hall’s cross-cultural communication. The research found out that Korea and the U.S are culturally divergent countries where there are significant differences in institutions and ways of communication.

The preservation approach for integration is recommended as Samsung’s objective of the acquisition is to expand its market by exploiting TWS’ resources and technology while preserving the identity and autonomy of TWS. Also, it is recommended to adopt low-context communication when exchanging information between Samsung and TWS to prevent misunderstanding resulted from cultural differences. In this way, it is expected that both companies can benefit from each other’s resources and knowledge more efficient and effective way.

Reference List

Amah, O. E., & Oyetunde, K. (2019). Human Resources Management Practice, Job Satisfaction and Affective Organisational Commitment Relationships: The Effects of Ethnic Similarity and Difference. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 45(0), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v45i0.1701

Bae, J., & Rowley, C. (2001). The Impact of Globalization on HRM: The Case of South Korea. Journal of World Business, 36(4), 402–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1090-9516(01)00064-5

Barkai, J. (2008). What’s a Cross-cultural Mediator to Do? A Low-context Solution for a High-context Problem. Cardozo Journal of Conflict Resolution, 10(1), 43–90.

Beers, B. (2021). What Is the Telecommunications Sector? Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/070815/what-telecommunications-sector.asp

Browaeys, M. J., & Price, R. (2019). Understanding Cross-Cultural Management. (4th ed.). Pearson Education Limited.

Chang-Howe, W. (2019). The Challenge of HR Integration: A Review of the M&A HR Integration Literature. Journal of Chinese Human Resource Management, 10(1/2), 19–34. https://doi.org/10.1108/jchrm-03-2019-0009

Country Watch. (2021). United States Country Review (pp. 1–1275).

Craft. (2021a). Samsung Electronics Competitors. https://craft.co/samsung-electronics/competitors

Craft. (2021b). TeleWorld Solutions. https://craft.co/teleworld-solutions

Crawley, E., Swailes, S., & Walsh, D. (2013). Introduction to international human resource management. Oxford University Press.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

Dudovskiy, J. (2017). Samsung Segmentation, Targeting and Positioning: multi-segment, imitative and anticipatory. Business Research Methodology. https://research-methodology.net/samsung-segmentation-targeting-positioning-multi-segment-imitative-anticipatory/

Dun & Bradstreet. (2021). Teleworld Solutions, Inc. https://www.dnb.com/business-directory/company-profiles.teleworld_solutions_inc.c6b3772653a5ebfab3618387086e93fe.html

Edwards, T., & Rees, C. (2005). International Human Resource Management: Globalization, National Systems and Multinational Companies. Pearson Education Limited.

Fredriksson, J., & Weidman, U. (2014). Understanding How to Handle the Acquisition Process (pp. 1–54) [MSc Thesis].

Greenwood, R. (2017). The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism (C. Oliver, T. B. Lawrence, & R. E. Meyer, Eds.; 2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Griffin, L. J., & Kalleberg, A. L. (1981). Stratification and Meritocracy in the United States: Class and Occupational Recruitment Patterns. The British Journal of Sociology, 32(1), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.2307/589761

Griffin, R. W., & Pustay, M. W. (2020). International Business: A Managerial Perspective. Pearson Education.

Hall, E. T., & Hall, M. R. (1990). Understanding Cultural Differences. Intercultural Press Inc.

Hall, E. T. (1973). The Silent Language. Anchor Books.

Haspeslagh, P. C., & Jemison, D. B. (1991). Managing Acquisitions: Creating Value through Corporate Renewal. Free Press.

Hofstede Insights. (2021). Country Comparison. https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/south-korea

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and Organizations. McGraw-Hill Professional Publishing.

Hwang, K. K. (1996). South Korea’s Bureaucracy and the Informal Politics of Economic Development. University of California Press, 36(3), 306–319. https://doi.org/10.2307/2645694

Kaufman, B. E. (2015). Market Competition, HRM, and Firm Performance: The Conventional Paradigm Critiqued and Reformulated. Human Resource Management Review, 25(1), 107–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2014.08.001

Kim, N. (2009). Multicultural Challenges in Korea: The Current Stage and a Prospect. International Migration, 52(2), 100–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2009.00582.x

Köster K. (2009). International Project Management. Sage Publications.

Lasserre, P. (2018). Global Strategic Management (4th ed.). Macmillan Education.

Lee, K. U. (2002). Economic Development and Competition Policy in Korea. Washington University Global Studies Law Review, 1(0), 67–76.

March, J. G., & Olsen, J. P. (1984). The New Institutionalism: Organizational Factors in Political Life. American Political Science Association, 78(3), 734–749. https://doi.org/10.2307/1961840

Merkin, R. S. (2009). Cross-cultural Communication Patterns – Korean and American Communication. Journal of Intercultural Communication, 20, 1–14. http://www.immi.se/intercultural/

Mesch, D. J., Perry, J. L., & Wise, L. R. (1995). Bureaucratic and Strategic Human Resource Management: An Empirical Comparison in the Federal Government. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 5(4), 385–402. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a037256

Morgan, J., Sisak, D., & Várdy, F. (2012). On the Merits of Meritocracy. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1–45. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2045954

Reiche, B. S., StahlG. K., Mendenhall, M. E., & Oddou, G. R. (2016). Readings and Cases in International Human Resource Management (6th ed.). Routledge.

Samsung Electronics. (n.d.). Company Info | About Us. Samsung Electronics. https://www.samsung.com/uk/about-us/company-info/

Samsung Newsroom. (2020). Samsung Acquires Network Services Provider TeleWorld Solutions to Accelerate U.S. 5G Network Expansion. Samsung Newsroom. https://news.samsung.com/global/samsung-acquires-network-services-provider-teleworld-solutions-to-accelerate-us-5g-network-expansion

Samsung Newsroom. (2021). FAST-FACTS. https://news.samsung.com/global/fast-facts

Schelhas, J. (2002). Race, Ethnicity, and Natural Resources in the United States: A Review. Natural Resources Journal, 42(4), 723–763. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24888656

Schuler, R., & Jackson, S. (2001). HR issues and activities in mergers and acquisitions. European Management Journal, 19(3), 239–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0263-2373(01)00021-4

Scott, W. R. (2014). Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests and Identities. Sage Publications.

Shin, G. (2006). Ethnic Nationalism in Korea: Genealogy, Politics, and Legacy. Stanford University Press.

Statcounter GlobalStats. (2021). Mobile Vendor Market Share Republic of Korea. https://gs.statcounter.com/vendor-market-share/mobile/south-korea

TeleWorld Solutions. (2019). What We Do. TeleWorld Solutions. https://www.teleworldsolutions.com/what-we-do/

Treger, G. (2020). Business Consulting – Q1 2020. In Clear Sight Advisors (pp. 1–8). https://clearsightadvisors.com/app/uploads/2020/05/Clearsight-Business-Consulting-Update-Q1-2020.pdf

Wilkinson, A. (2019). The SAGE Handbook of Human Resource Management (N. Bacon, S. Snell, & D. Lepak, Eds.; 2nd ed.). Sage.